Students’ Materials

- Writing journal, with plenty of paper and/or your laptop

- A previous draft of one of your poems

Room Setup

Six “stations” will be set up at even intervals around the room, each with its own set of instructions. They will be identified by the following names:

- Anaphora

- Heavy Enjambment

- Sentence Fragment

- Lack of Punctuation

- Cut

- Splice

Instructions

There will be six rounds of writing, each lasting 10 minutes. For the first round, Group 1 will be at Station 1: “Anaphora,” Group 2 at Station 2: “Heavy Enjambment,” etc. For subsequent rounds, the groups will rotate to new stations in numerical order. Students should have their previous poem draft and writing notebook at each station. Upon arriving at a station, each group member should read and follow the instructions on the card. After completing the assignment, you should have revised your previous draft into a whole new poem. If there’s time, each student should share their new, revised poem.

Station 1: Anaphora

Read your poem draft, and circle a phrase that is the most charged, most crucial to your poem. Re-write the poem and introduce a repetition of this phrase or syntactical unit. Read Joy Harjo’s “She Had Some Horses” for an example.

Station 2: Heavy Enjambment

Locate all of the end-stopped lines in your poem and circle them. Remove half of those end-stopped lines by breaking the line elsewhere in the sentence and thereby introducing enjambment. Take a look at Ross Gay’s “Love, I’m Done With You” for an example; pay special attention to incidence of enjambment in the first seven lines.

Station 3: Sentence Fragment

Turn at least two complete sentences in your poem into sentence fragments. See Chen Chen’s “Self-Portrait as So Much Potential” for an example of a poem that employs many sentence fragments.

Station 4: Lack of Punctuation

Remove the punctuation in all or half your poem, like Morgan Parker in “Take a Walk on the Wild Side” or “If You Are Over Staying Woke” respectively.

Station 5: Cut

The poet Jean Valentine tapes her poems up on her door after she initially drafts them. Every time she passes the poem, she cuts one word. In the next ten minutes, cut at least five words from your poem. Read her poem “God of Rooms” for inspiration.

Station 6: Splice

Steal 1–2 lines full or partial lines from a group member’s poem. Try to make them work in the dramatic situation of your poem. Check out Matthew Olzmann’s “Letter Beginning with Two Lines by Czesław Miłosz” as an example.

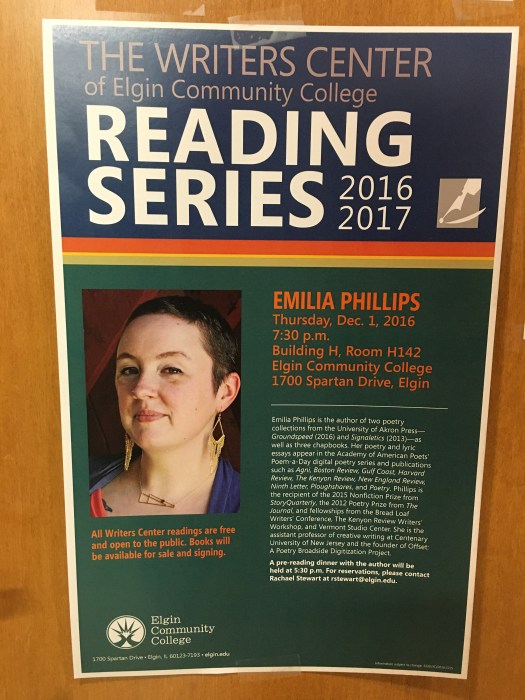

On Wednesday, November 16, I gave the lecture “It’s Alive: Why Poetry Still Matters” at Rutherford Hall in Allamuchy, New Jersey. Here are the materials for that talk:

On Wednesday, November 16, I gave the lecture “It’s Alive: Why Poetry Still Matters” at Rutherford Hall in Allamuchy, New Jersey. Here are the materials for that talk: