Instructor’s Course Description

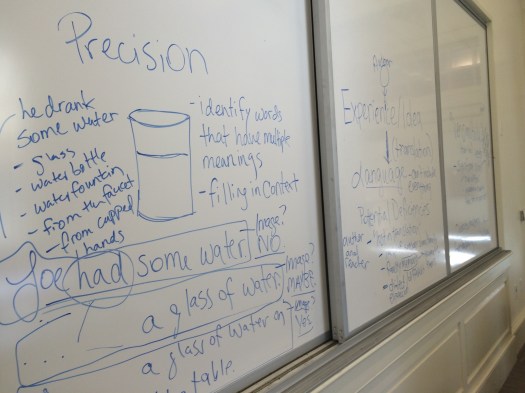

As a means of exploring the craft of prose writing, we will read, analyze, and imitate two living writers: Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie and Jesmyn Ward. By reading two, book-length works by each writer—a short story collection and book-length essay by Adichie and a novel and memoir by Ward—we will see how these writers develop their unique styles across genres and locate how their personal concerns inform their fictional narratives. Additionally, we will supplement these texts with short stories and essays by some of the most influential prose writers of the 20th century to understand the history and development of American prose over the last one hundred years. We will translate these immersive reading experiences into writing skills through discussion, exercises, and workshop. Several times throughout the semester, students will turn in original writing for workshop, a collaborative discussion about writing techniques and their effects on readers, and later revise two of the pieces using the comments received in workshop. You should bring to this class a hard work ethic supported by curiosity and generosity. We will base our discussions on how texts work rather than what they mean, after Francine Prose’s ideal of “reading like a writer.” My approach to teaching writing is founded on the belief that our writing skills must be practiced and cultivated, and that one must continually challenge one’s aesthetics, habits, and concerns throughout one’s writing life in order to write anything of consequence to one’s readers and, perhaps more importantly, one’s self.

Required Texts

- The Thing Around Your Neck by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Anchor, 2010. ISBN: 978-0307455918

- We Should All Be Feminists by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. Anchor, 2015. ISBN: 978-1101911761.

- The Best American Essays of the Century, ed. Joyce Carol Oates. Mariner, 2001. ISBN: 978-0618155873.

- The Best American Short Stories of the Century, ed. John Updike. Mariner, 2000. ISBN: 978-0395843673.

- Men We Reaped: A Memoir by Jesmyn Ward. Bloomsbury USA, 2014. ISBN: 978-1608197651

- Salvage the Bones by Jesmyn Ward. Bloomsbury USA, 2012. ISBN: 978-1608196265

Grade Requirements

- Class Participation (10%)

- Group Presentation (15%)

- Four Workshop Pieces (40%)

- Two Revisions (15%)

- Two Imitations (10%)

- Discussion Board Participation (5%)

- Final Reading (5%)