“Encounter” Exercise

Class: Introduction to Creative Writing (The College of William & Mary)

Genre: Fiction

Purpose: To explore Burroway’s concept of “Character as Image”; examine potential of non-verbal communication; and situate the reader to receive information along with a character

Readings: Chapters 4 (“Character”) and Gabriel García Márquez’s “The Handsomest Drowned Man in the World” in Janet Burroway’s Imaginative Writing

Two characters come upon one another in the middle of a forest. Something bad—but not melodramatic*—has happened to one character and that character needs help. When the first character tries to tell the second what’s wrong, it’s revealed that the two characters don’t speak the same language. (This could include sign language.)

Write a scene from the point of view of the second character (first person “I”) while the first character tries to communicate the problem using only gestures, drawing, or other non-verbal communication. Additionally:

- the second character cannot know what the problem is before the first character reveals it in this scene;

- the second character should notice details throughout the interaction that reveal more about the first character (i.e. clothing, appearance, possessions, etc.)

- the second character may or may not—or even cannot—help.

*Challenge yourself to come up with a problem that doesn’t involve far-fetched plot lines, flat characters, and easy conclusions. This means it would be best to avoid killers, aliens, and monsters. Think about more ordinary but equally tension-filled situations like a farmer whose lost a bull, a teenager who has a flat tire but doesn’t know how to change it, a hunter who accidentally shot his buddy in the foot, etcetera.

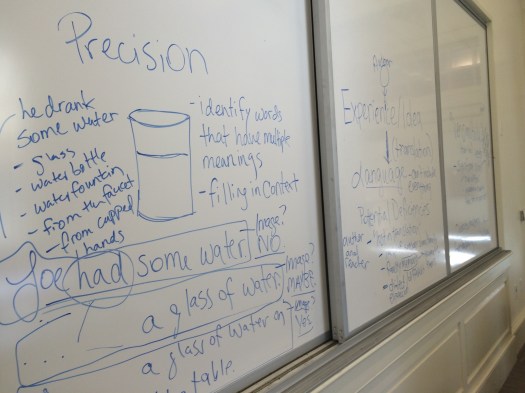

“Joe had some water”: Intro to Creative Writing Discussion about Image, Specificity, Significance, and Precision

After talking about Janet Burroway’s Image chapter in Imaginative Writing, my class took our discussion to the white board to consider problems with translating experience and ideas in language, the fundamentals of significant detail, and the precision of language.

I asked them to consider all of the possible meanings for each of these sentences:

“Joe had some water.”

—He drank some water; he has water to drink; he had water for watering his plants, etc.

“Joe had a glass of water.”

—He drank the glass of water; he had a glass of water to drink, etc.

“Joe had a glass of water on the table.”

—He had water to drink on the table and he hadn’t finished drinking it.

We explored the slippery nature of the word “had” in all of these cases, and then we thought about how context could change the sentences. We considered the difference between “a glass of water” versus a “water glass,” how the second doesn’t necessarily mean that the glass contains water, rather it could designated as a glass for water. Additionally, having the read come to “glass” before “water” would help form the image for the reader as it provides the container before what’s contained inside it.

“Backwards Story a Telling” Exercise

Class: Introduction to Creative Writing (The College of William & Mary)

Genre: Fiction

Purpose: To open up discussion about plot structure and significant details

Readings: Chapters 9 (“Fiction”) and 6 (“Story”) in Janet Burroway’s Imaginative Writing

- Watch a viral video without taking notes. (“Texting Guy Almost Runs Into Bear”: http://youtu.be/WYsAkjfXxzU)

- Write a summary of what happens in the video. (2 min.)

- Now write a scene from the point of view of the bear or the man. Try to tap into their thoughts and moment-by-moment perceptions. Include as many details as you can in 5 minutes. Here’s the hitch: you must tell the story in reverse chronological order! (Tell the story backwards!)

- Look at the inverted check mark diagram of pg. 173 in Burroway. Discuss how the check mark works for a chronological story compared to the story told in reverse. Where does the conflict fall in your scene? The crisis (climax)? Is there resolution? Were there any details you thought of telling the story backwards that you might not have thought of telling the story chronologically?

“One Story, Three Genres” Exercise

Class: Introduction to Creative Writing (The College of William & Mary)

Genre: Fiction, Nonfiction, and Poetry

Purpose: To consider how writers of three genres go about approaching similar subject matter; to introduce distinctions between the genres; and to introduce key drafting and revision considerations based on reading from Janet Burroway’s Imaginative Writing

Readings: Chapters 1 (“Invitation to the Writer”) and 7 (“Development and Revision”) in Janet Burroway’s Imaginative Writing

- Pick a favorite nursery rhyme, myth, or religious tale that you know by heart. Write a brief summary of the story in 2 to 5 sentences.

- If you were writing this narrative as a short story, how would you change it? What elements would you include? How would the style change?

- If you were writing this narrative as a poem, how would you change it? What would be your first steps to writing the poem? What would you leave out? What would you add in?

- If you were using this narrative as a basis for nonfiction, how would you frame it? How can you approach this subject matter in that way?

- Free write for ten minutes and begin to convert your summary into either a short story, a poem, or personal essay.

“Fame Makes a Man Take Things Over” Exercise

Genre: Creative nonfiction

Readings: A packet of persona poems and dramatic monologues

Time: 10 minutes

1. Pick a celebrity, sports star, cartoon or comic book character, product mascot (ex. Count Chocula, the Geico gecko, etc.) or newsworthy individual (Octomom, Charles Manson, etc.).

2. Create a mundane problem for that character or person. (Kobe Bryant can’t open a jelly jar. Elvis Presley can’t fit into his old slacks. Speedy Gonzalez gets stuck in a mouse trap.)

3. Free write for ten minutes in the voice of that character as they’re attempting to resolve the problem. What concerns them? Are they worried about their public image? How does this problem relate to bigger problems for them? What sorts of language do they use? Are they thinking about the problem at hand or something else? Where are they at? More specific questions: What are they wearing? What kind of jelly is Kobe Bryant trying to get into? Strawberry or grape? Who set the trap for Speedy? Has Elvis tried dieting? (Hint: You don’t have to answer these specific questions, but be sure to take leaps like this with your own characters.)

Tearing Down the Walls Exercise

After a spirited discussion of the first six chapters of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities that included forays into questions of genre, style, and (with a little help from a Bachelard excerpt on “Intimate Immensity”) reality, my Writing Out of the Ordinary students took a break from their creative thinking to do some creative writing.

1. Pick one of the cities in Invisible Cities that you find the most outlandish, strange, or compelling.

2. Create a character that lives in one of these cities. Give that person a role in the community (i.e. a job, unemployment, a family, friends, etc.). Now write a brief sketch of no more than a page about a day in that character’s life. Make sure you take into account the unusual aspects of the city. Does the character visit the room of crystal globes in Fedora? What does the inhabitant of Baucis see looking at the ground? What are the goodbyes like when the people of Eutropia move to another identical city?

3. Now imagine that the fabulist foundation starts to erode. Write a narrative in which the city starts to become what we would think of as “normal” but which seems outlandish and strange to its inhabitants. Start small but by the end have the inhabitants’ whole reality challenged. Example: Maybe the inhabitants of Eutropia open the gates of their city with the intent of moving to the next one only to realize that there’s no other city nearby.

Because we ran out of time, the students will continue to work on 3 at the beginning of the next class. Once they are done writing, I’d like to add a fourth step to the exercise:

4. Reflect. What are the implications of the change for the character? Are interpersonal relationships changed? The character’s role? Is the character able to adapt to the changes? To what extend does that character cling to the old way of life? Is the change good or bad? In some small way, is the character a new character because of the new context? Does the old city live on in, still exist because of, the character’s memories and imagination?

I’m anxious to see what they come up with, especially because of the ouroboric discussion of invention and reality. I can’t help but think of Calvino himself writing that “a story is . . . an enchantment that acts on the passing of time, either contracting or dilating it.” With time, of course, comes change, and so at its root the exercise may be an exercise in time, an enchantment recharmed, an hourglass flipped on its head.

Italo Calvino on introversion

“Certainly literature would never have existed if some human beings had not been strongly inclined to introversion, discontented with the world as it is, inclined to forget themselves for hours and days on end and to fix their gaze on the immobility of silent words.”

—Italo Calvino, “Quickness”

On Journaling: a Revelation

Journaling is an exercise in being a character.

In keeping a journal, I distance myself from the self that appears in my writing. (Think Dante the writer vs. Dante the character.) This not only allows me to receive critical input without feeling as if I’m under attack but it also, and perhaps more importantly, gives me the opportunity to view my own writing as a reader would.

Maybe other writers out there have come to this realization, but the idea, and the way I was able to say it, surprised me in its clarity. Maybe this too is a product of journaling: I have distanced myself enough so that I am allowed to be surprised by myself, a moxie I find quite germane to the writing of the lyric.

Metamorphosis Exercise

Today in Writing Out of the Ordinary the class animatedly discussed Kafka’s “The Metamorphosis” and Márquez’s “A Very Old Man with Enormous Wings.” During the last twenty minutes of class, they participated in the following exercise that asks them to transform a character into another creature in the spirit of Gregor Samsa’s overnight transformation or à la the “fearful thunderclap” that “rent the sky in two and changed her into a spider”:

1. Outline the narrative of an extraordinary—think of “extraordinary” in terms of its literal meaning, “outside the normal course of events”— event (the time when . . . i.e. you broke your arm skiing, you shared an airport shuttle with the mayor, the woman sitting next to you in 16A threw up on the plane window during takeoff, etc.).

2. Now, pick a character that you’re willing to change.

3. Turn that character into another creature (ghost, sheep, centaur etc.) but allow the world to stay familiar. Rewrite it with that in mind. What changes? What can stay the same?

4. Now, reflect. Is there a way to get to something you couldn’t by making this change? Does it change what’s at stake in the piece? How did you attempt to keep the world realistic even when there was a fantastical creature in the scene?

I also emphasized that the realism in magical realism isn’t simply that the context of magical creature is realistic but that the magical creature is also depicted in a way that seems real to that world of the story. What’s realistic in a fictional space can be different than what’s realistic in our lives. Other thoughts I encouraged: How does one keep the narrative squarely in the world of magical realism and not drift into fantasy? How does one prevent the fantastical creature from being thought of as only allegory? We’ll continue to think about these things as the magical realism unit progresses.